Friday, December 27, 2013

"Revenge: Eleven Dark Tales" by Yoko Ogawa

Revenge: Eleven Dark Tales [1998] by Yoko Ogawa and translated [2013] by Steven Snyder reminds me of the publications under the title Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Each pub would have a series of strange short stories that at the end of each tale-depending on the quality of the writing-I'd say to myself something like "that's strange," or "that's wierd," or after awhile "saw that coming." However, Ogawa's Revenge leave its readers with more. The stories taken together show the mysterious, macabre and sometimes murderous links that hold a society together and could be considered part of the definition of community itself. Although The Washington Post Book World's review compares Ogawa's book to Haruki Murakami's writing, the tales in this book seem to have more in common with Ryu Murakami's work and the whole violent genre of Japanese noir fiction. In its own way, Revenge creates a dark reality that shows why Japanese noir fiction makes sense. I encourage you to read it.

<br/><br/>

<a href="https://www.goodreads.com/review/list/18120142-joe-cummings">View all my reviews</a>

Monday, November 18, 2013

"Driving Mr. Albert" by Michael Paterniti

When I was growing up in the 1950s and 60s, Albert Einstein

was one of the two dead celebrities/ heroes that we all knew. He was the guy

who looks like an eccentric but lovable great uncle who was super-intelligent

because he used a greater percentage of his brain than the rest of us mortals.

Everyone admired Albert Einstein.

Michael Paterniti's "Driving Mr. Albert" [2000] is

an examination of the cost and curse of celebrity. The book focuses around

Professor Albert Einstein and Doctor Thomas Harvey-the Princeton pathologist

who performed the autopsy on Einstein in 1955. As a part of the procedure, he

removed Einstein's brain from the skull to weigh and measure it. Afterwards, he

took Einstein's brain home with him for further research. Decades later, he

still had it. For Paterniti, the pathologist is an “uberpilgrim” who is nearing

the end of his peregrination.

Basically this is an account of the strange road trip that the

author and Harvey made in a Buick Skylark from Princeton, New Jersey, to the

Bay Area in California with Einstein's brain stashed in truck sloshing around in

a Tupperware container. It is also a meditation on the lives of Einstein,

Harvey and the author. Paternity also makes some interesting observations on

the nature of celebrity and the 21st Century world which Einstein helped shape.

This was a fun book to read, and I recommend this slightly macabre but humorous

tale.

Friday, September 27, 2013

"Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth" by Reza Aslan

No doubt like many other people, I first heard about Reza

Aslan and his book Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth (2013) on

NPR in reference to an interview he had had on Fox News. For a week or so, a

ridiculous controversy arose about if a Moslem could write about what

Christians call the Old and New Testaments. My feeling is that anyone who can

find a publisher can write and publish a book about whatever he wants. The

question should be is it a book worth reading.

In Zealot, Aslan sets out to separate the historical Jesus

of Nazareth from Jesus Christ the Son of God around whom modern Christianity is

formed. It’s a reasonable inquiry. After I returned from a pilgrimage in Spain

in 2000, I started rereading the Christian Bible and became interested in the

historical Jesus, too. And like Aslan, I read John Dominic Crossan’s works The

Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant and Jesus: A

Revolutionary Biography as well as other books and articles by Crossan and other

writers. To me, it has been and still is a rewarding exercise that has helped

my meditations each time I read the New Testament.

The search for the historical Jesus of Nazareth is an

incredible challenge. After all, the books the New Testament itself were

written after the crucifixion. Nevertheless, Aslan has done an excellent job of

extracting the Galilean from what was written about him after his death and

placing him within his own social, economic, political and religious times.

Aslan then makes some interesting conclusions about the rise of Jesus Christ the

Son of God after the death of Jesus of Nazareth also by looking at the

historical times when the letters of Paul, the four gospels and the rest of the

New Testament were written (with the exception of Revelations).

Besides the narrative itself, Aslan includes a meaty

“Author’s Notes” section where he discusses his sources and some of his

reasoning and conclusions. He also has a lengthy bibliography of the books and

articles that he has read for those readers who are also interested in taking

up the modern quest for the historical Jesus of Nazareth.

Since coming back from Spain in 2000, I have tried to read

the Christian Bible every year and I try to read the New Testament an

additional time during the Lenten season. Before starting that exercise (but

sometimes during or after), I enjoy reading some other book which will

stimulate my own meditations about what I’m reading. Aslan’s Zealot would be

a worthwhile read before reading the New Testament, and I heartily recommend

it.

When I finish reading any book, there are three questions

that I ask myself: Is this book worth buying? Is this book worth rereading?

Would it be worthwhile to read something else by the same writer? My answers

for Zealot: The Life and Times Jesus of Nazareth are yes, yes and yes.

Friday, September 20, 2013

Tuesday, August 6, 2013

summer morning rain

summer morning rain

drops wash away desert dust

overcast skies gray

soothing restorative balm

soothing

restorative

calm

Sunday, July 28, 2013

"A Moveable Feast" by Ernest Hemingway

I decided to read A Moveable Feast after reading and enjoying Enrique Vila-Matas’ novel Never Any End to Paris which was inspired in part by this Hemingway favorite . In some ways, it was about time. I had known about the attraction of this book and the idea of a young artist run off to the Left Bank to find his self. Julio Cortazar had done just that in the 1950s; his reminiscents are recorded in Hopscotch. Roberto Bolaño leaves his impression of being in Paris in The Savage Detectives. A descendent of Hemingway used the title in a similarly-titled cookbook filled with recipes for picnic foods. When you consider how poor and hungry Hemmingway was during his time in Paris, the appropriation of the memoir’s title might be considered facetious.

The book was written at the end of the author’s life and published after his death. It’s about the beginnings of his literary career when he was working on his first great novel The Sun Also Rises. With him in Paris were other members of the Lost Generation (so named by his mentor Gertrude Stein) including James Joyce, Ford Maddox Ford, Ezra Pound and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Besides recounting his adventures and impressions with them and others, the memoir is a testimony to his love for his first wife Hadley and the time they spent together in the City of Light.

This was a good book; I recommend it to all Hemingway fans.

Friday, July 26, 2013

"Never Any End to Paris" by Enrique Vila-Matas

Like Ernest Hemmingway in the 1920s and Julio Cortazar in

the 1950s, well-known and award-winning Spanish writer Enrique Vila-Matas spent

two years in the 1970s finding himself by losing himself in the City of Lights.

The author recounts his adventures and misadventures in the 2003 novel Paris

no se acaba nunca which was translated by Anne McLean in 2011 as Never Any

End to Paris. The book is supposed to be a tale about a modern day writer who

is giving a seminar workshop on irony. By the end of the book, however, that façade

has faded away, and the author is talking directly to his readers about his

experiences.

What a strange and wonderful time this young man had living

in the Left Bank during the 1970s in a garret at the house of Marguerite Duras

as he wrote his first novel. He crossed paths with people like playwright Samuel

Beckett, author Jorge Luis Borges, actress Jean Seberg, costumer designer

Paloma Picasso and other well-known people who were drawn to Paris as a center

of culture and celebrity. He also knew many other young artists who would later

become famous, but at that time they were just getting started in their

respective careers. In fact, I encourage you to have your computer or tablet

handy to google the different people that you’ll encounter in this book. I did,

and now I have a new list of books I want to read.

This is a wonderful book that runs the gamut of reminiscences

from laugh-out-loud funny to quite quite sad. It is also in its own way a very

good study of irony and an interesting meditation on the craft of writing.

"Cloud Atlas" by David Mitchell

I became interested in Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell after seeing the preview of the movie starring Tom Hanks, Halle Berry and others. While reading the book, I got to see the movie, and while both were good, they however were quite different. But let me come back to that.

Mitchell describes what the Cloud Atlas is the book as a "sextet for overlapping soloists . . . each in its own language of key, scale and color. In the first set, each solo is interrupted by its successor: in the second, each interruption is recontinued, in order. Revolutionary or gimmicky? Shan't know until it's finish, and by then it'll be too late."

What results is a set of six novellas one nested inside another that extend from the 19th Century to somewhere in the future. Each story is linked to the story that occurs before it in time. Each story has its own distinct language and style. And each story is linked together by having one its characters have in a birthmark in the shape of a comet that represents the universal theme of all six stories. Here is where the book differs from the movie.

In the movie, the uniting theme is union of a love between two souls. That theme is better expressed, though, in Laura Esquivel's La Ley del Amor [The Law of Love], a great book that's also cleverly presented. This book’s uniting theme, however, centers around the idea that there are two types in this world: those that exploit and those that are exploited be it by bullies, murderers, cultural institutions, corporate greed, genetic engineering or whatever. The comet birthmark represents the resistance to being exploited unjustly, or as Dylan Thomas wrote:

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Mitchell describes what the Cloud Atlas is the book as a "sextet for overlapping soloists . . . each in its own language of key, scale and color. In the first set, each solo is interrupted by its successor: in the second, each interruption is recontinued, in order. Revolutionary or gimmicky? Shan't know until it's finish, and by then it'll be too late."

What results is a set of six novellas one nested inside another that extend from the 19th Century to somewhere in the future. Each story is linked to the story that occurs before it in time. Each story has its own distinct language and style. And each story is linked together by having one its characters have in a birthmark in the shape of a comet that represents the universal theme of all six stories. Here is where the book differs from the movie.

In the movie, the uniting theme is union of a love between two souls. That theme is better expressed, though, in Laura Esquivel's La Ley del Amor [The Law of Love], a great book that's also cleverly presented. This book’s uniting theme, however, centers around the idea that there are two types in this world: those that exploit and those that are exploited be it by bullies, murderers, cultural institutions, corporate greed, genetic engineering or whatever. The comet birthmark represents the resistance to being exploited unjustly, or as Dylan Thomas wrote:

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

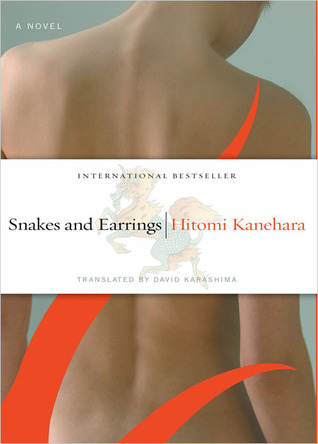

"Snakes and Earrings" by Hitomi Kanehara

This is an odd disturbing little book. In fact, I had to

read it twice. Hitomi Kanehara’s 2005 novel Hebi ni piasu, which was

translated by David James Karashima also in 2005 as Snakes and Earrings, is

set in the dark side of Tokyo’s youth culture. The narrator is a young

woman named Lui who recounts her relationship with Ama, a boy friend who she

met at a strange bar. He was the scariest-looking guy there.

Besides having a face full of earrings, Ama has an unique

body modification: his tongue is forked at the end like a snake’s; he also has

a large distinctive-looking dragon tattoo. Lui becomes fascinated and follows

Ama home. The next day they go to meet Shiba-san who is the artist that gave

Ama both his split tongue and large tattoo.

So it is, that Lui who up this point been a Barbie girl

type-complete with blonde hair-is drawn into the punk/goth world of Japanese counterculture

and into the lives of two very dangerous men. What disturbed me about this book

after the first reading was Lui’s seeming ennui and nihilism. Like Meursault in Camus’ The Stranger, Lui

simply reports what happens to herself and the world around her in a

matter-of-fact way. She also reminded me of what NPR commenter Andrei

Codrescu once said that one reason why goths and punks like tattoos and body

piercings was that the pain of receiving them was the only thing that broke

through the ennui.

On the second

reading, however, I decided that Lui was no Meursault. She tries to shape the

world around her so she can live the way she wants to live. And while she wants

to be different, she knows that there are boundaries. When Ama tries to give

her an inappropriate token of his affection, for example, she responds “That’s

no symbol of love. At least not in Japan.” So there are limits to her

rebellion.

This is author

Hitomi Kanehara first novel. It won the prestigious Akutagawa Prize. She is the

youngest writer to win this important Japanese literary award. Interestingly

one of the judges was Ryu Murakami. His first novel Almost Transparent Blue also

won the Akutagawa Price back in 1976. His book, not surprisingly, was as disturbing as Snakes

and Earrings.

This book was a

good read; I look forward to reading more by Hitomi Kanehara.

Friday, July 19, 2013

Review of "Basho: The Complete Haiku"

reading Basho’s poems

learning on a summer’s

day

I ‘m a poor haijin

The 2008 collection Basho: The Complete Haiku by

Matsuo Basho is translated by Jane Reichhold with an introduction,

biography and notes. This is an excellent introduction to traditional Japanese

haiku. Basho (1644-1694), after all, was an early practitioner and developer of

this unique poetic art form; he set many of the standards for this type of

poetry that are still practiced today.

Reichhold, a honored haijin (i.e. haiku writer) in her own right, has

gathered all of Basho’s haiku under one cover. Surprisingly there are only

1012. After an interesting introduction, the haiku are presented in chapters

that describe seven different stages or passages of the poet’s life.

Then the verses are examined again in Notes where each haiku

is shown in Japanese, Romanized Japanese for the sound counters, and in

English. Each poem has the year it was written and to which season it belongs

along with expository notes to explain the subtlety of the verse in terms of

history, symbols and the Japanese language. Reichhold also provides a

descriptive list of 33 haiku techniques to help the reader to better appreciate

the art form as well as other useful back matter. This is an excellent book

that I would add to my personal library.

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

first monsoon passes

first monsoon passes

glorious sunset follows

cool breeze promises

half moon hidden overhead

more storms journey in the dark

Sunday, July 14, 2013

Modern Japanese Tanka by Makoto Ueda

First you have to understand that all “tanka” is “waka,” but

not all waka is tanka. Both forms are 31 syllable verses that generally follow

a 5-7-5-7-7 format, but waka is an ancient type of poetry that has been a

Japanese literary tradition for centuries. Waka poetry can be found in the

“Kojiki,” Japan’s oldest book. Tanka,

however, is a new literary genre that came out of the late 19th

Century by a restless generation of poets that found traditional waka to be

stale and repetitive.

In his excellent book, “Modern Japanese Tanka” Japanese

scholar and Stanford professor Makoto Ueda discusses the development of tanka

from the late 19th Century to modern times. He shows how it differs

from “haiku,” and more importantly how tanka is a more liberating and versatile

art form. He does this with 400 samples by twenty different poets. In each

chapter, Ueda introduces and describes the contribution of a different tanka

master.

Tanka can be very haiku-like with the use seasonal

references and cutting words, like Yosano Akiko’s:

evanescent

like the faint white

of cherry blossoms

blooming among the trees

my life on this spring day

Tanka, more importantly can also be about anything

else-especially about the emotional reactions to the events and environment

around the poet. When military veteran Mori Ogai ironically recalls his military

service, he writes:

some medals

compensate for the terror

of the moment

while others pay for many

humdrum days spent in the service

A tanka writer can also poke fun at his own foibles. The reader

can almost see Maekawa Samio slap his forehead as he recounts and complains:

monumental

idiot that I am

I’ve sent an umbrella

to a bicycle shop

for repairs

Tanka can also capture Life’s poignant moments. Yosano

Tekkan writes of the loss his six-week old daughter in “To our baby that died:”

in the dark woods

lying ahead on your road

whom will you call?

you don’t know yet the names

of your parents or your own

It should be pointed out that translated tanka can look like

free verse, and some tanka are. Editor Ueda helps those readers concerned with

the 31 syllable constancy of the verses by presenting each poem in English and

in Romanized Japanese at the bottom of the page.

Facebook friends know that I have been captioning with verse

some of the photos I make of a ten kilometer walk along the canals between my

home and the local library. It’s a therapy of sorts. The photos remind me to

keep searching for beauty during this terrible time of being unemployed. The captions/lyrics/verse/poems

were, at first, in the style of seventeen syllable “haiku,” but recently I’ve

been offering some poor samples tanka as well. It’s a more suitable form

sometimes. I know that from reading this book.

Friday, July 12, 2013

The Breath of God by Jeffrey Small

While religious studies are important, fiction based on

religion is also a useful meditation. “The Breath of God” by Jeffrey Small is a

novel about a religious studies grad student who finds ancient documents in a

remote Himalayas monastery suggesting that Jesus of Nazareth studied with

Brahmin and Buddhist masters before starting his own ministry in Palestine. The

idea that the “Son of God” was not divinely inspired or worse inspired by pagan

religions infuriates a bible thumping minister from Alabama and some of his

followers. They attempt to undermine and sabotage the student’s efforts to

bring the proof to the West. So

basically this is a fictionalized account of the Religious Right meets the

Jesus Seminar on a smaller scale.

The book is well researched; it draws off the works of

Marcus Borg, Thich Nhat Hanh, John Shelby Spong, Paul Tillich and others.

Besides being action-packed and having a romantic interest throughout, the book

is also a discussion of the commonality of all modern religions. This

commonality is based on a commonality of experience shared by the founders of

various religions. There is also the suggestion that every person has the

ability to know the godhead through prayer and meditation. So, if you’ve

already read the latest Dan Brown and you’re interested in religion, I

encourage you to read this book.

For another novel that deals with the unknown years in

Jesus’ life, let me suggest the light-hearted “Lamb: The Gospel According to

Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal” by Christopher Moore. It also is an action-packed

well-researched meditation on what Jesus might have experienced before starting

his ministry. For a more macabre telling by an atheist, see “The Gospel

According to Jesus” by José Saramago. These books are good thought-provoking summer

reads.

Friday, May 31, 2013

"Real World" by Natsuo Kirino

In the summer of 1992, I studied International business in

Tokyo, Japan. Every school day, I would commute into the city on the train

along with mostly businessmen, office girls and high school students who were attending

cram school. After a while, the students on the train figured out that I was an

approachable friendly sort of guy, and a few of the braver ones tried chatting

with me to practice their English. I didn’t realize it at first, but as I talked

with one or two of the students, their classmates were listening very carefully

to what we were saying. Once I made a joke that the person with whom I was talking

didn’t catch, but one of the eavesdroppers did. When she laughed, we all turned

to look at her, and being embarrassed for having brought attention to herself

and her curious classmates, she melted into the crowd of students behind her.

During that long ago summer, it occurred to me that young

Japanese women suffer a harder row to hoe than most American high school women

or, in fact, other Japanese. They had to meet the social expectations that the

rest of their generation has to suffer, but they also had to suffer an arrogant

sort of Japanese male chauvinism. This ranged from TV cameramen who would run

their cameras up and down the legs and made sharp close ups on the cleavage of

pretty girls to the discreetly paper-cover manga that men and boys would read

on the trains. These comic books often had terrible scenes of pornographic sex

and sexual violence.

At the same time, these young women-like all young people everywhere

sought for ways to express their unique individualism. This was expressed many

ways from decorating personal items with “Hello Kitty” to dressing as Brazilian

samba dancers in a summer Bon Festival parade. When a person is young and under

enormous social pressure to conform and meet the expectations around him or

her, it is normal to band together with friends to enjoy and express an unique

and separate identity.

This is the premise of “Real World,” the 2008 translation by

Phillip Gabriel of “Riaru Warudo” the 2006 novel by Natsuo Kirino. This is the

story of four high school girls who live in metro Tokyo and have been best

friends forever. They don’t belong to any other clique or group and they all

are attending the same summer cram school as they prepare for college entrance

exams. Beyond that, each one feels that she is unique. Each has her own

terrible secret which she believes the others don’t know and wouldn’t

understand. The others know or least suspect, of course, but it’s not mentioned

because they’re friends.

One of the girl’s neighbor is an unremarkable boy who

attends a more prestigious high school, The girls have nicknamed Worm. One day,

he is accused of violently beating his mother to death, but before the crime is

discovered, he steals the girl’s bicycle and cell phone while apparently

leaving the crime scene. As a result, the four girls become involved in

different ways with the young murder suspect as he goes on the run. Each girl

in her own way has her life changed when they completely confront the reckless violence

of the real world.

I enjoyed reading “Real World,” and I look forward to

reading more by Natsuo Kirino who has been described as a feminist noir writer.

In some ways, this novel is like “Catcher in the Rye” meets “In Miso Soup.” After

all, J.D. Salinger was an adult who wrote about being a runaway kid and

Japanese author Ryu Murakami wrote about an American mass murderer loose in

Tokyo. Kirino was in her mid-fifties when she wrote “Real World.” So perhaps

this is just a cautionary tale that confirms the worst stereotypes of Japanese

high school life. I would have felt different about “Real World” if it had been

written by a woman who was in her twenties. Still it resonates as true when one

of the girls tells her BFF that “With death staring me in the face, I finally

understand the reason novelists write books: before they die they want

somebody, somewhere, to understand them.” In the end, don’t we all in the real

world.

Wednesday, May 29, 2013

22/11/63 by Stephen King

Author Stephen King and I are members of the same

generation-we are both sons of what has been called “the greatest generation.

And just as every member of the greatest generation can recall where they were

on December 7, 1941 when they heard the news that Pearl Harbor had been bombed,

every member of my generation can recall where they were when they heard the

news that the greatest member of the greatest generation President John F.

Kennedy has been assassinated.

For me, I was in class that day at George Mason Junior/Senior

High School in Falls Church, Virginia. The public address system came on

abruptly throughout the building, and we were told that classes were going to

be cancelled that day. Then we were instructed to go to our last period classrooms

and to wait to be dismissed [i.e., wait for the school busses to arrive] there.

When I got to my last period classroom, there was a turned on TV, and my

classmates and I watched as CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite tried to explain to

the world what was going on in Dallas. JFK had been shot. It was the teary watershed

event of my generation.

I remember the quiet bus ride home keeping my emotions from

welling up; I remember yelling for mom with tears in my eyes and voice when I

got home; I remember the incredulous look on her face when I told her the horrible

news.

My grandmother and great aunt were coming up to visit that

weekend, and they with my parents and brother went over to nearby Washington DC

for the funeral. I couldn’t go. I was too torn up-too sadden-by the death of

the president.

Instead, I stayed home and watched everything on the

television. I saw the photograph of LBJ being sworn into office on Air Force

One with Jackie standing by in her blood-stained dress; I saw the rider-less

horse, and I saw little John saluting as his father’s funeral cortege rolled

past; I saw Lee Harvey Oswald being shot down himself by Jack Ruby. I saw it

all. My whole generation did, and our hearts ached.

For me and I believe for others, it was a hurt that took a long

time to heal. And afterwards any mention of the assassination stirred up

sadness for me. Even songs like “Abraham, Martin and John” and “American Pie”

brought back sad memories of that tragic day. Now I know the song is about the

plane crash that took the life of Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and the Big

Bopper, nevertheless I was reminded of JFKs funeral and Jackie dressed in black

every time I heard the lines:

…Bad news on the

doorstep - I couldn't take one more step

I can't remember if I cried when I read about his widowed bride

Something touched me deep inside the day the music died

I can't remember if I cried when I read about his widowed bride

Something touched me deep inside the day the music died

And I think that a lot of people thought what would have

happened if the music hadn’t died that day in Dallas and if JFK had lived

through his trip to the Lone Star State. It would have been a different world,

a better world. For instance, a lot of people like to believe that JFK was too smart

and pragmatic to have allowed America to be drawn into the Vietnam War. This is

the premise of Stephen King’s book “11/22/63.” A young school teacher is shown

a way to travel back to the late 1950s. After he’s told that by saving Kennedy

he would save everyone who had died during the war in Southeast Asia, he

accepts the commission to go back and prevent Lee Harvey Oswald from shooting

JFK.

As he waits he learns the great, good, bad and evil about

those happy days. Diner food compared to modern fast foods was delicious. Cars

looked so cool. Everything was cheaper. Everybody smoked cigarettes. The air in

every factory town was more polluted. Segregation segregated. Most importantly

the teacher realized that everybody was oblivious to what was terribly obvious

to him.

In this strange new world of a half century ago, the teacher

falls in love with a colleague while at the same time he stalks Oswald and waits

for his moment of destiny with the assassin. What will he do after Dallas? Will

he live in past or should he try to take her back to this time of the Internet,

hip-hop and Starbuck on every corner. The past is obdurate and difficult to

change. Likewise one has to consider “the butterfly effect” which hypothesizes

that even the slightest thing a person does now [whenever that might be] may/might/will

have a great effect on what happens in the future.

I usually read King’s novels when I’m on vacation or want to

take a break from the books that I usually read. They are like brain candy-something

light and easily digested. Still, some of his books like “The Green Mile” are

wonderfully poignant; “22/11/63” was one of these.

I have to confess I

enjoyed King’s travelogue through time. After all, that was my boyhood, and

like all Americans, I tend to be more nostalgic and ahistorical than I should

be. Still, I can remember being back then in that classroom waiting for the buses

to pick us up. My classmates and I learned more about the horror and idiocy of

violence and hatred than we ever did watching westerns on the television. We

had been ignorant to the world good and bad around us. We shouldn’t be now.

As the fiftieth anniversary of JFKs assassination nears it’s

worthwhile to think back to that terrible day. It stills makes me sad. And I

know all of the forthcoming books, TV specials and cute, commercial, commemorative

crap that will be available soon are going to sadden me more. After all, that

was my boyhood. Still, Stephen King’s “22/11/63” is a useful reminder that we

cannot change what has happened without changing what’s happening now and what may/might/will

happen next.

Thursday, May 23, 2013

"Infinity in the Palm of her Hand" by Gioconda Belli

“Infinity in the Palm of her Hand [2009]” is a translation

by Margaret Sayers Biden of “El infinito en la palma de la mano” by Gioconda

Belli. This interesting book is a feminist look at the story of Adam and Eve

from the sentience of the first man to shortly after the first homicide recorded

in the Bible. The author says that she was inspired to recount the tale after

coming across some books that she found in her father-in-law’s library. Perhaps

she had perused ancient writings based on the Mishnah, or perhaps it was Mark

Twain’s “The Diary of Adam and Eve.” We don’t know. Nevertheless, her browsing

inspired the author to ponder those first familiar chapters of Genesis.

The Other [aka Elokim] makes Adam to tend his garden; the

creator then makes Eve from Adam. He communicates with his creations not

through discourse and conversation but mainly by intuition and dreams. While the

first man and women do not possess the knowledge of Good and Evil, they

understand that fruit of two trees in the garden are forbidden to them.

Eve is also advised by a feathered serpent who claims that

she has been with Elokim since the time before there was a garden. Curiously,

the creature speaks to the woman in enigmatic caveats, and so Eve is forced to

make her own decisions. The serpent also tries to explain Elokim’s ways and

motives, but she also urges the human to “Accept your solitude, Eve. Don’t

think of me, or of Elokim. Look around you. Use your gifts.”

Adam accepts Eve’s choices, and pragmatically he tries to adjust

to the real world when Paradise is taken away. Although he is a problem solver,

there still are thoughts of returning to the garden lingering in his heart.

Gioconda Belli, a poet, creates lovely descriptions of the

changing worlds that surround her characters. Additionally, she does a great

job when recounting the challenges that threaten violence that were faced by

mankind’s first family in the real world. She, however, doesn’t follow Genesis

chapter and verse as she tells her tale. As a result, the book ends in an unusual

way.

In the Author’s Note at the beginning of the book, Belli

cautions her readers that her story is not Creationist or Darwinist, it is

fiction, and as fiction this is a fun and worthwhile novel. It is important to

read and meditate on stories in the Bible. It’s also important to read other

people’s meditations-both scholarly and lay-on the Scripture. With that in

mind, I encourage you to read “Infinity in the Palm of her Hand” as you make up

your own mind how it was in the beginning.

Monday, May 13, 2013

Necropolis by Santiago Gamboa

“Necropolis, “ a translation by Howard Curtis of Necrópolis

by the Columbian writer Santiago Gamboa , is a strange book indeed, especially

when you consider that it is the first of Gamboa’s work to be published in

English. What launched its publication was its winning the La Otra Orilla

Literary Award in 2009. At that point Gamboa was [and still is] considered an

important writer in the new McOndo school of Latin American writing. Although

some of his works are available in translation in seventeen other languages,

this is his first novel that has been translated into English.

Basically, it is the story of a writer [the narrator] who

attends an academic conference on biography at the King Davis Hotel in

Jerusalem. The city is caught in a battle between the dividing political and

religious forces of the time. So in the middle of the death, dying and

destruction that occurs in a war zone an academic meeting on the study of life

is convened.

At the meeting are the usual intellectual types that normally

are found at such literary events, but there also are some unusual attendees as

well, including an ex-con religious leader and an Italian porn star. This is reminiscent

of the “Decameron” or “Canterbury Tales” where a group of people are isolated

together each with his own tale to tell.

Actually, such literary references abound throughout the

novel. Gamboa is a philologist like Jorge Luis Borges, and like Borges, Gamboa

has seeded his text with false and real literary references from Uriah Heep to

Simonides for his readers to find. He also sometimes not too subtly lifts plot

lines from classics like Alexandre Dumas’ “The Count of Monte Cristo.”

After the first day of the conference, one of the attendees

dies under mysterious circumstances, and the narrator sets out determine the

real reasons for his demise. As he searches for answers regarding the suicide

or murder of his co-participant, the conference continues while the war outside

rages on and grows closer and closer to the King David and the meeting.

Necropolis has been compared favorably with Roberto Bolaño’s

“Savage Detectives.” [One of Gamboa’s first literary references is a tip of the

hat to the great Chilean/Mexican writer.] And the book is clearly in the new

McOndo style. Most of the characters are very cosmopolitan Latin Americans

moving around on a global stage. Still Bolaño’s work was grittier and more

realistic, and the ending of “Detectives” was more satisfying-at least for me. “Necropolis’ ends on a dark and stormy night

which may be Columbian’s last joke with the reader. Still, “Necropolis” is a

very good book. The narrative quickly captures and maintains the reader’s

interest, and the story flows despite the biographical interruptions of the

participants at the conference. Indeed these narrative detours are in

themselves interesting. I look forward to reading more by Santiago Gamboa.

Monday, May 6, 2013

SIn: The Early History of an Idea

"Sin: The Early History of an Idea"[2012] by Paula Fredriksen is an interesting but challenging read about how the concept of sin changed over the first four hundred years of Christian history. Fredriksen looks at Scripture and other the extant writings concerning seven people: Jesus of Nazareth and Paul of Tarsus in the first century, Valentinus, Marcion, and Justin the Martyr of the second century, Origen of Alexandria in the third century and Augustine of Hippo in the fourth.

Jesus and Paul were two first century leaders that believed that the apocalypse was at hand. Jesus, as he is recorded in the gospels, was concerned with the fate of the Jewish people. Paul, on the other hand, concerned himself in his writings with the fate of gentiles and the rest of creation. So their ideas on sin differed.

After the rise of Constantine and his conversion to Christianity in 312 CE, the church in Rome sought to “orthodoxize” the extant writings of earlier Christian writers. In Marcion, they practically succeeded; very few of his works remain. As a result, this type of analysis is particularly difficult when it comes to the second century writers. Nevertheless there remain plenty of writings by orthodox writers condemning his “heresies,” and it is from those writings that the author has made some interesting conclusions about him, Valentinus and Justin. Each represents a different view based on the facts that Jerusalem had been destroyed and Jesus had not yet returned.

Finally she looks at the prolific writings of Origen and Augustine. Both are worthy of examination. Augustine was the last great mind of the early Christian era. The Vandals who had earlier sacked Rome were practically at his door in Hippo as he lay on his deathbed. Nevertheless, his writings survived him and “became a font of subsequent Latin Christian doctrine.” As such, they continue to affect modern definitions of sin and virtue, condemnation and salvation, and the nature of a severe, all-powerful God, etc. Origen also remains important. Starting from the same sources as Augustine, his writings and conclusions represent “a road not taken by the church.”

People who enjoy reading about theology, philosophy, language, ideas and early church history will enjoy this book.

Sunday, May 5, 2013

Red April

RED APRIL

Edith Grossman's translation of Santiago Roncagliolo’s

award-winning novel "Abril rojo" is a great read. The book is a

Kafkaesque murder mystery about one man's journey into the horror that has

lingered in Peru after the rise and fall of the Sendero Luminoso [Shining

Path], a rural Maoist revolutionary group.

The story takes place in a rural township in the foothills

of the Andes during March and April 2000. Associate District Prosecutor Felix

Chacaltana Saldivar is a civil servant who was raised in Lima. A year before,

however, this minor functionary had asked for and had received a transfer back

to the town of his birth in rural Peru. His main professional concern is to

quietly and inoffensively succeed within the local federal bureaucracy. His

other ambitions are to be a good son to his mother and to win the heart of a

local waitress that he just met.

As Holy Week 2000 approaches, he is forced to investigate a

particularly gruesome murder. As a result he is drawn into the world around

him. This is a world which still harbors some of the social and political horrors

that have been a part of Peru’s history before, during and after the rise of

the Shining Path in the 1980s.

Chacaltana changes as the novel progresses from a milk-toast

civil servant to someone like the inhabitants of the world around him; people who

yearn “for a kind of power, a kind of domination, the feeling that something

was weaker than he was, that in the midst of this world seemed to swallow him

[Chacaltana] whole, he too could have strength, potency, victims.” The novel

has an ending that is unexpected but satisfactory.

Like I said, this book is a great read, and I heartily

recommend it. Edith Grossman’s translation is, as always, excellent,

Roncagliolo was born and raised in Peru. He discusses growing up during this

sad time in “Deng’s Dogs.” The essay can be found in the aptly named “Horror”

issue of “Granta” 117. By the way, Roncagliolo left Peru to live in Barcelona, Spain in 2000. "April rojo" was first published in 2006. Grossman's translation was first published 2009.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)